Isolated – Isolationserfahrung Geflüchteter Menschen in Brandenburger Gemeinschaftsunterkünften

(4 Folgen)

Paula Küntzel & Jakob Tuchelt

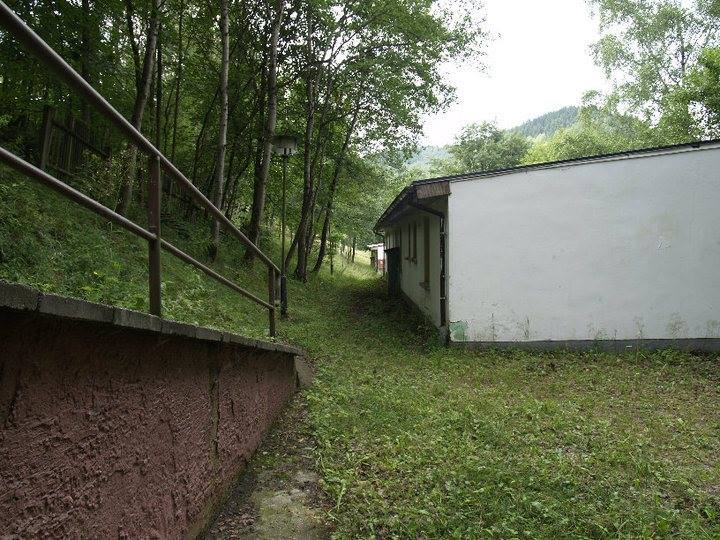

Dieses Bild hängt mit folgender Bildunterschrift im Refugees Emancipation Community Center:

This is what the road to the Kunersdorf camp Looks like. The Trip from Potsdam takes between 3hrs. and 4hrs. When you arrive at the nearest bus Station you habe to walk around 20 minutes to reach the camp. The last bus to leave the area leaves at 6pm.

So sieht der Weg zum Kunersdorfer Heim aus. Die Fahrt von Potsdam dauert zwischen 3 und 4 Stunden. Wenn man an der nächst gelegenen Bushaltestelle ankommt, muss man noch etwas 20 Minuten laufen, um das Heim zu erreichen. Der letzte Bus, der die Gegend verlässt, fährt um 18:00.

[…] not only […] refugees are isolated from the communities. The communities are also isolated from the refugees. It works both ways. the asylum system sort of like puts a barrier. It puts a border.”

Fiona Kisoso (Refugees Emancipation e.V.) im Interview.

Die öffentlichen Debatten zum Thema Flucht und Migration erhalten insbesondere seit 2015 viel Aufmerksamkeit. Was dabei jedoch häufig außen vor bleibt sind die Stimmen von Geflüchteten selbst. Im Rahmen des studentischen Forschungsprojekts Isolated – Isolationserfahrung Geflüchteter Menschen in Brandenburger Gemeinschaftsunterkünften berichten Geflüchtete von ihren Perspektiven. Wir werfen in den Interviews einen Blick auf die Isolationserfahrungen, die Geflüchtete in Gemeinschaftsunterkünften machen. Dabei wird klar: nicht nur die Geflüchteten sind von der deutschen Gesellschaft isoliert, sondern auch andersherum die deutsche Gesellschaft von den Geflüchteten. Isolationsmechanismen wirken in beide Richtungen.

Die Erfahrungen der Geflüchteten, mit denen wir gesprochen haben, werden in vier unterschiedlichen Folgen hörbar gemacht und wissenschaftlich eingeordnet. Dabei geht es thematisch um räumliche Isolation (Folge 2), psycho-soziale Isolation (Folge 3) und Isolation von Information (Folge 4). Die erste Folge dient als Einführung in das Thema und wurde sowohl auf deutsch als auch auf Englisch aufgenommen. Die restlichen Folgen sind nur englischsprachig.

Unter räumlicher Isolation (Folge 2) verstehen wir alle räumlich-infrastrukturellen Aspekte der Isolation, zum Beispiel Isolationserfahrungen, die Unterbringung, Lage und Anbindung von Geflüchteten und Geflüchteten-Unterkünften betreffen. Diese zeigt sich vor allem durch die abgelegenen Wohnheime für Geflüchtete und fungiert sowohl als Form der Isolation Geflüchteter von der deutschen Zivilgesellschaft als auch andersherum.

Als psycho-soziale Isolation (Folge 3), bezeichnen wir all die Aspekte der Isolation, die soziale Kontakte, körperliche und psychische Gesundheit, Hoffnungen, Selbstverwirklichung und Lebensgestaltung (z.B. in Bezug auf Sprachkurse und Arbeitsmarktchancen) betreffen. In dieser Folge kommt besonders stark zur Geltung, wie die Isolation auf Geflüchtete wirken kann und wie verwoben ihre verschiedenen Aspekte sind.

Die Isolation von Informationen (Folge 4) meint die Erfahrungen, die mit dem (Nicht-)Erlangen von für die Geflüchteten relevanten Informationen zusammenhängen. Dies können beispielsweise Informationen über den Aufenthaltsstatus, Sprachkurse, Arbeitsmöglichkeiten und soziales Leben sein. Diese essentiellen Informationen sind teils in den Unterkünften und der erreichbaren Umgebung nicht verfügbar; gleichzeitig ist auch der Fluss von Informationen nach Außen stark gehemmt.

In allen drei Folgen zeigt sich, wie groß die Bedeutung von rechtlichen und institutionellen Hürden und Barrieren (legal block) auf der einen Seite und Rassismus-Erfahrungen, Ausgrenzungen und Vorurteilen (mental block) auf der anderen Seite sind, die die Isolation von Geflüchteten wesentlich mitbestimmen und aufrechterhalten.

Mit dem Podcast wollen wir einen Beitrag dazu leisten, Informationen aus den Geflüchtetenunterkünften herauszutragen und somit das Wissen in der deutschen Gesellschaft über die Isolationserfahrungen Geflüchteter zu vergrößern. Im Zentrum unseres Beitrags stehen daher die Erfahrungen von vier Geflüchteten und wie sie diese selbst einordnen.

[…] at the end of the day, I am me. I can’t be you.I am Black.I cannot turn into white to please you.At the end of the day, I have my own personality.I have my own person.I am my own person.

Ana (anonymisiert) im Interview

Das Projekt wurde in enger Zusammenarbeit mit Refugees Emancipation e.V.[1] durchgeführt. Unser Dank richtet sich besonders an Fiona Kisoso, Immaculate Chienku, Louise Nzele und Eben Chu. Ohne ihre Beiträge und Hilfe wäre das Projekt nicht umsetzbar gewesen.

[1] Refugees Emancipation e.V. ist eine politische Organisation, die von Geflüchteten gegründet und organisiert ist. Ihr Ziel ist es, sich über viele verschiedene Wege für eine Verbesserung der Lebenssituationen Geflüchteter in Deutschland, spezifisch Brandenburg, einzusetzen.

Folge 1: About „Isolated“

Transkript des Audios

Podcast-Script: Isolated– Isolationserfahrungen von Geflüchteten in Brandenburger Unterkünften Ein Podcast von und mit Paula Küntzel und Jakob Tuchelt

Folge 1: About “Isolated” Teaser: [Fiona]: “Having have lived in a von Heim for maybe, It sort of feels like you’ve been frozen in time. You cannot really move forward. You cannot move back. You’re stuck in a place.” [Ana: “you’re not allowed to do anything. You’re not allowed to, you’re not allowed to maybe move away from the camp.” [Theo]: “Most of the time, I’m alone. I´m alone. When I go to school, I come back. I’m always alone” [Ana: “as much as people have issues they’re dealing with, but the camp is not helping much” [Fiona]: “you’re qualified you went to school you have so much to offer that doesn’t matter” [Theo]: I must start the course in February. So I lost one year. (..) I didn’t do anything. [Fiona]: “the isolation is not only one way that refugees are isolated from the communities. The communities are also isolated from the refugees. the asylum system sort of like puts a barrier” Einleitung [Auto rauschen] [Paula]: Wir fahren in das tiefe Brandenburg, dort wo wir hinfahren, liegt eins der vielen Camps, in dem Geflüchtete während ihres Asylverfahrens wohnen. Unser Plan ist heute unsere Interviewpartner*innen für diesen Podcast kennenzulernen. [Jakob]: Aber erst einmal: wer sind wir überhaupt? Wir, sind zwei Soziologiestudierende der Uni Potsdam, die euch durch diesen Podcast leiten werden. Ich bin Jakob. [Paula]: Und ich bin Paula und wir heißen euch herzlich willkommen zu unserem Podcast Isolated- Ein Podcast über die Isolationserfahrungen geflüchteter Menschen in Brandenburger Unterkünften. [Jakob]: Diese erste Folge soll euch einen allgemeinen Eindruck auf unser Thema verschaffen und bereits einige Hintergründe beleuchten. In den Folgen 2,3 und 4 sprechen wir dann über verschiedene „Typen“ oder Aspekte von Isolation: Physische Isolation, Psycho-Soziale Isolation und in der letzten Episode über die Isolation von Informationen! Im Dezember letzten Jahres lebten 16.586 Geflüchtete in Gemeinschaftsunterkünften und 335 in vorübergehenden Unterkünften in Brandenburg. Für diesen Podcast haben wir mit 4 von diesen Menschen Interviews aufgenommen, die wir zu ihren persönlichen Erfahrungen befragt haben. Außerdem haben wir ein Interview mit Fiona Kissoso und Imma Chienku aufgenommen, die aus ihrer professionellen Erfahrung über dieses Thema sprechen können. [Paula]: Ein paar der Interviews in dieser Folge wurden auf Englisch geführt, ab etwa der Mitte dieser Folge werden wir daher auf englisch sprechen. Der Podcast wird außerdem ab der zweiten Folge dann ganz auf Englisch stattfinden. Aber zurück zu unserer Reise: Nach Brandenburg mitgenommen werden wir von Imma und Fiona, die wir eben schon erwähnt haben. Beider arbeiten beim Verein Refugees Emancipation. Das ist eine politische Organisation, die von Geflüchteten selbstorganisiert ist und sich über viele verschiedene Wege für eine Verbesserung der Lebenssituationen Geflüchteter in Deutschland einsetzt. Wenn ihr mehr über die Organisation erfahren wollt, schaut gerne auf Facebook und Instagram nach und hört in den Podcast unserer Kommilitoninnen Emma und Leonie rein. Im Geflüchteten Camp angekommen, lernen wir nicht nur zwei unserer späteren Interviewpartner kennen, sondern im Kontext von Refugees Emancipation sprechen wir auch mit ihnen und weiteren 5 Bewohnern über ihre Situation vor Ort und im Asylverfahren. Direkt danach unterhalten wir uns über das Treffen: Reise: [Rückblende zu Audioaufnahmen von uns, direkt nach dem Besuch in dem Heim] [Jakob]: Gerade sind wir in Rathenow. (..) Wir sind anderthalb Stunden oder eine Stunde mit dem Auto hergefahren. Durch ganz dichten Nebel. (..). [Paula]: Am Eingang mussten wir unsere Personalausweise abgeben. Also zumindest vorzeigen. Dann haben wir alle einen Besucher:innenausweis bekommen. [Jakob aus dem off]: Wir fragen Imma auf der Rückfahrt, warum diese formale Anmeldung erforderlich ist: [Imma im Auto]: warum man das machen soll, weiß ich nicht. Ja. Aber, (..) ich habe mich auch nie richtig gefragt, warum, aber vielleicht bin ich einfach gewöhnt, dass es so passiert in 99 von Unterkünften, dass sie einfach mal wissen wollen, wer reinkommt und wer rausgeht. (.) Ja. Aber warum macht man sowas? (..) Das weiß ich nicht. (.) das ist immer eine Frage von Sicherheit, vielleicht von der Heimbetreiber. Dass das sind so gefährliche Orte, wie wir immer bei Refugees Emancipation das nennen. Es ist kein normaler Ort, weil du siehst, normaler Ort muss man sich nicht ausweisen. Ja. Aber das sind, in Einführungszeichen, gefährliche Orte, muss man gucken, wer da reinkommt. Es ist ein Kontrollmechanismus, (.) glaube ich. [Jakob aus dem off]: Wir haben also am Eingang unsere Personalien abgegeben. [Paula]: Ja, und dann sind wir hochgegangen in ein Zimmer, was sehr… (.) Sehr klein. Sehr klein ist. Drei Betten. Sehr spärlich eingerichtet. das sah eigentlich so aus wie… Ich habe drei Sachen und ich bin gestern hier angekommen. [Jakob]: Ja, da war kein Kleiderschrank. Oder irgendwas war… [Paula]: Gar kein Schrank. [Jakob]: Ein Tisch und drei Betten waren da drin, ja. [Paula]: Das Fenster ging nicht auf. (.) [Jakob]: Aber es gab eine Herdplatte. [Paula aus dem off]: In diesem Zimmer hatten wir dann unser Treffen mit ca. 7 Interessierten Bewohner:innen der Unterkunft. [Jakob]: Hättest du damit gerechnet, dass sich jetzt so viele Leute erstmal prinzipiell bereit erklären, mitzumachen? (…) [Paula]: Ich habe da gar nicht so drüber nachgedacht, muss ich sagen. [Jakob]: Ich habe voll viel drüber nachgedacht. (.) [Paula]: Also ich hatte auch den Eindruck, was ich schön fand, dass die Leute sich auch relativ sicher gefühlt haben, so Sachen von sich zu teilen. Ich schätze mal auch ganz viel dadurch, dass Ima und [Fiona] dabei waren, die ja auch selber nicht weiß-deutsch sind, sondern auch selber natürlich da. [Jakob]: Das habe ich die ganze Zeit gedacht, wenn die nicht da wären, wir wären sowas von aufgeschmissen gewesen. [Paula]: Ja, also verständlicherweise ist es ja viel leichter, sich jemandem zu öffnen, von dem du weißt, der hat irgendwie vielleicht ähnliche Erfahrungen gemacht wie ich und der weiß ein bisschen, wie es auch sein kann. Und das können wir beide ja gar nicht wissen. [Jakob aus dem off]: An dieser Stelle ist es vielleicht angebracht zu sagen, dass wir beide, [Paula] und ich, weiß sind und, wie unsere Eltern, in Deutschland geboren und aufgewachsen sind. Dementsprechend mussten wir noch nie die Erfahrung machen, dass Rassismus unser Leben oder unseren Alltag in irgendeiner Weise einschränkt. [Paula aus dem off]: Wir fragen auch Imma und Fiona nach ihrem Eindruck von unserem Besuch. [Jakob]: Wie war sonst euer genereller Eindruck? Oder dein Eindruck? [Imma]: Mein Eindruck, also, hat mir gut gefallen, weil, (..) normalerweise sind die Geflüchtete sehr, sehr ängstlich. Sie, sie gucken immer mit, ähm, Vorsicht, (.) wer, wer, wer seid ihr? Ähm, soll ich versagen? Soll ich meinen Namen? Das kann, manchmal ist es sehr unterschiedlich. Du kommst in eine Unterkunft und die Leute, sie kommen zwar, aber, sie gucken sich sehr merkwürdig, (.) […] es ist nicht immer so, dass die Leute kommen und sich öffnen. Weil, mit diesem Asylsystem ist sehr viel Angst verbunden. Man weiß nicht, wer. (.) Dann, es sind immer Gerüchte, sie sind Leute von der Regierung. Vielleicht, wenn du gehst, ähm, du sagst deine eigene oder deine richtige, ähm, ähm, Daten, und dann wirst du dann abgeschoben. Aber, hier habe ich gesehen, die Leute waren offen. [Paula]: Was sind dann noch für Ängste hinter? Also, abgeschoben zu werden. Gibt es noch andere Ängste? (.) [Imma]: Ähm, (…) die abgeschoben, (….) ja, ich glaube, das ist das, am meisten von den Ängsten. Genau. Ähm, vielleicht kriege ich kein Geld mehr. Ich fürchte um meine Existenz hier. Ich möchte kein Problem. Ähm, meine Situation ist zwar nicht gut, aber, ähm, wie man immer sagt, lass die liegenden Hunde schlafen. [Paula]: Also möglichst nicht auffallen, und so den Kopf runterhalten, um möglichst keinen Stress zu bekommen. [Imma]: Genau, Ja! [Paula]: And Fiona, what were your impressions of the visit? [Fiona]: yes um from our our visit today you notice there was no women yeah already so you can already see the degradation of just how much that lifestyle in the heim affects people in different um at different levels there’s gender there’s you know. So women actually, they fall through the cracks they’re they’re more marginalized yeah there’s you know there’s a degradation from just being a refugee to being an african refugee woman living in isolation in brand new book has repercussions and you see that today because we actually did not see one. Not even in the compound yeah not even on the Treppenhaus at all like when we’re coming up you don’t see them at all so you ask yourself where are they? [Paula]: what do you think where they are? [Fiona]: they’re taking care of their children or like maybe they are in depression or maybe they are so afraid that things spaces like this they feel like it’s not for them. I’m sure [Name] did not just call men. Or even if he did these other ones already could have called the women they know who live in the heim, but there must be uh something at play here. I mean, it’s not a long time ago we were here. For me, what a little bit shocks me is just how low the mood of the people is. They’re not positive and they don’t have information about their status. They feel isolated information-wise. That for me was a little bit negative. It didn’t feel good to see it like that. But it gives me a positive impression to see that they want to make the situation better. They want… Another thing is I also did not like that we still have this control to give our Ausweises and what not. Because for me it means that the practice to make refugees look like their lives are dependent on their stay here on like their administration. The administration have all the say on their lives. Aufbau des Podcasts – Was wir von der Reise mitgenommen haben [Jakob]: From now on our moderation will also proceed in english. During our first visit and the conversation with Imma and Fiona afterwards, we identified 3 Types of Isolation. In a separate Interview Fiona called them physical isolation, psychosocial isolation and isolation from information [Paula]: So, with these categories in mind we will look at our interviews in the next few episodes. In the next episode “physical isolation” we will talk about the circumstance, that a lot of Refugee Camps in Brandenburg lie remote, far away from possibilities of public transportation and often in areas with a bad network and internet connection. We will also talk about restricted legal possibilities to move and the signal, that is given to the german public by all those forms of physical isolation. [Jakob]: In the third episode, “psychosocial isolation” we will look more closely at the psychic and social effect of isolation on refugees. We will deal with the following topics: feeling of lonelyness and belonging, personal relationships, and mental and physical health. But also we will talk about how an experience of racism affects everyday life and security. Through this we want to show the connection between isolation and its mental consequences. [Paula]: The fourth and final episode deals with the isolation of information. Refugees often have limited or no access to essential sources of information. The consequences of this, which important hubs are emerging and who is particularly affected, are our topics in episode number four. [Jakob]: So, as you can hear, we have a lot planned. You can listen to all of these episodes separately; we have produced them in such a way that they can be understood independently. But of course, all of these aspects are connected and together create a bigger picture. [Paula]: And that brings us to the end of this first overview episode. [Jakob]: We hope we’ve sparked your interest. Until then— We see you in the next episode. [Both]: Bye Bye. Ending [Ana: “at the end of the day, I am me. I can’t be you. I am black. I cannot turn into white to please you. At the end of the day, I have my own personality. I have my own person. I am my own person. So, really, for me, I don’t, I don’t, um, really think so much about it. But, of course, when it happens, yes, there’s a way you feel. You can’t deny that.” [William]: Je voudrais que les Allemands et les étrangers vivent comme des frères. (.) Et n’aient pas de haine. Peut-être pour quelque chose qui s’est passé il y a 100 siècles. (…..) [ENG]: I want Germans and foreigners to live as brothers. (.) And not to hate each other. Perhaps for something that happened 100 centuries ago. (…..) Acknowledgements [Paula]: We would like to thank: Refugees Emancipation for their tremendous support of the project, the connections, and their work. Special thanks go to: Fiona Kisoso, Immaculate Chienku, Louise Nzele, and Eben Chu We also thank our interview partners: Ana, Stephane, Theodore, and William for their trust and cooperation! Thanks to Tobi, Theo and Anna for the voice-over. A big thank you to Yohane Nkuibo, Max Guggenheim and Deirde Winter for translating the French interviews. For mixing and technical assistance, we thank Johannes Tuchelt [Jakob]: Isolated is a podcast produced by Paula Küntzel and Jakob Tuchelt in cooperation with Refugees Emancipation, for the Department of Social Structure Analysis at the University of Potsdam.

Dieses Bild hängt mit folgender Bildunterschrift im Refugees Emancipation Community Center:

To reach Hohenleipisch you have to travel between 3.30hrs and 4hrs. The road is lonely and there is no easy access to Services such as supermarkets, pharmacies, doctors, educational centers, etc. A group of refugees were traveling from this camp to Potsdam to have to german, i. e., 8 Hours of daily travel for three months. Can you imagine yourself doing this every day?

Um Hohenleipisch zu erreichen, muss man zwischen 3.30 und 4 Stunden fahren. Die Straße ist verlassen und es gibt keinen einfachen Zugang zu Dienstleistungen wie Supermärkten, Apotheken, Ärzten, Bildungszentren usw. Eine Gruppe von Geflüchteten reiste von diesem Heim nach Potsdam, um dort Deutschunterricht zu nehmen, d. h. sie waren drei Monate lang täglich 8 Stunden unterwegs. Können Sie sich vorstellen, das jeden Tag tun?

Folge 2: Physical Isolation

Transkript des Audios

Podcast-Script: Isolated– Isolationserfahrungen von Geflüchteten in Brandenburger Unterkünften Ein Podcast von und mit Paula Küntzel und Jakob Tuchelt

Folge 2: Physical IsolationTeaser:

[Fiona]: “to be a woman or a child a refugeeliving in those isolatedjoint accommodations (..) is (….) it’s it’scapital offense if you ask me (.)” [Ana]: “you’re just, you’re in your room, you’re sharing a room with maybe eight other people, five other people, youre just in your room” [Theo]: “we have problems with trains and buses. At 8, 9 or 10, if you don’t get the possibility to come back, it is not easy for you to come back” [Fiona]: “the neighborhood and the towns where these von Heims are, (.) there’s a feeling that they’re over there, they’re hidden, that place far, because they’re dangerous. “ Introduction: [Paula]: Welcome back to episode 2 of our Podcast Isolated- a Podcast about isolation experiences of refugees in Brandenburg. I’m Paula. [Jakob]: And I am Jakob, and we study sociology at the university of Potsdam.. Looking Back into the last Episode: [Paula]: In the last episode we talked about our trip to a Refugee Camp and our impressions from that visit and we gave a general overview on our podcast topic. [Jakob]: Today, in the second episode, we will deal with the topic of physical isolation. We are going to talk about aspects of how and where Refugee Camps are located and about the impact and bigger meaning of physical isolation. Paula: All people we interviewed for this podcast on their personal experiences were anonymized by us and are being referred to under a fake name. We also want to address that both Jakob and me are white and, like our parents, were born and raised in Germany. Accordingly, we have never had to experience racism restricting our lives or our everyday routines in any way. Topic of this Episode [Jakob]: In this episode we will talk about physical isolation, specifically about moving between the different camps, in what ways a camp can be a home, spatial isolation, public transportation and the room situation within the camps [Paula]: Many refugees have to change their assigned place of residence multiple times within a short period of time, as was the case with Theodore: [Theo]: “I was arrived in Germany in 2022, 22, yeah. My first staying is in Eisen. I lived in Eisen two or three weeks after I was transferred in Frankfurt-Oder. In Frankfurt-Oder, I lived during four months after I was transferred in Premnitz in Brandenburg here.” [Jakob]: One First Reception Centre in the State of Brandenburg is located in Eisenhüttenstadt. Asylum seekers are accommodated in a first reception centre during the first few weeks of their asylum procedure. The actual asylum procedure itself is carried out by the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) in Eisenhüttenstadt. [Paula]: So that means: the state of brandenburg is only responsible for accommodation and basic care while the state germany is responsible for the asylum process. [Jakob]: law defines that Asylum seekers are distributed among the districts and independent cities after spending a maximum of six months in the first reception centre. However, this law is not always being adhered to: [Jakob]: “How long have you been in Germany or in a camp?” [Ana]: “I’ve been in Germany now for one year, one year, four months now. (..)I was in the first reception center for 14 months. (…..) Okay. (….)” [Jakob]: Unfortunately, we were unable to find official data on the mobility of women and children or on the mobility of people with temporary residence permits. We searched specifically for this information because we were told in the interviews that women and children tend to stay in the accommodation longer than men. [Paula]: What we were able to find is general data regarding the History of assinged shelter: A Study caried out by the Federal Ministry of Migration and Refugees published in 2022 collected data from refugees who came to Germany from 2013 – 2016. The survey took place in 2019 finds the following: Half of the initial moves from first reception centers to shared accommodations took place within the first 3 months after arrival (50%). For just under 40% of respondents, however, the first move takes longer than six months, and for 30% it takes a year and a half or longer. These figures correspond to the experiences shared with us by our interview partners. [Jakob]: How many refugees are being distributed to a federal state is determined by the so called Königsteiner Schlüssel. In Brandenburg thats three percent of the asylum seekers who came to Germany in the first place. At the first reception center, refugees undergo medical examinations before being distributed further. In the first reciption center the federal states are responsible for accomodation and basic care. After the stay in the first reciption center the responsibility of accomodation and care shifts to the districts and independent cities. Responsibility is therefore passed down. Except for the asylum procedure itself. Which, like already said, remains in responsibility of the federal level, meaning the state of germany. [Paula]: Refugees Cannot participate in the decision of where to live. Once they arrive in a federal state, the responsible authorities assign accommodation to the refugees. Stephane talks about this allocation of a home by the authorities. [Stephane]: “Non, mais pour l’isolement, il y a l’isolement. Parce que je suis toujours seul. Il faut que j’aille chercher le petit, là. C’est pour ça que je viens à Berlin. Moi, si ce n’est que moi, je ne devrais pas vivre à [Rathenau], moi. C’est parce qu’on ne peut pas décider, parce qu’on est en asile. Quand on voit que tu es obligé de partir, c’est ça. Sinon, quand je suis là-bas… c’est pour ça que je reste chez moi. Parce que je n’ai pas où partir, je suis isolé. » [ENG] No, but as regards the isolation, there is isolation. Because I am always alone. I have to go and find the boy, there. That’s why I come to Berlin. If it was just up to me, I wouldn’t live in [Ort]. It’s because you can’t decide because you’re in asylum. When they see that you have to leave, it’s that. Otherwise, when I’m there … that’s why I stay at my place. Because I haven’t got anywhere to go, I’m isolated. [Paula]: The allocation of a home is usually accompanied by restrictions on freedom of movement. [Fiona]: “a lot of people get ausweise with restrictions for movement. there was this, what they had, a residence fleeced, which was lifted. But because it was, it was lifted does not mean people still feel secure. You can just change a law, but then you don’t really let the people know, hey, you’re free” [Jakob]: Fiona refers to ‘residenzpflicht,’ which translates to ‘spatial restriction.’ Specifically, this means that as long as refugees are required to live in a reception centre, the so-called residenzpflicht applies. This is a curfew. Only when they are no longer required to live there, but no later than after three months, does this spatial restriction end. [Paula]: For refugees, this means that they need permission to leave the district of the responsible immigration authority. There must be compelling reasons for leaving. If refugees have to go to lawyers, authorities or courts and their personal appearance is required, an exception is made. [Ana]: “Yeah, you’re not allowed to do anything. You’re not allowed to, you’re not allowed to maybe move away. from the camp. At Eisen, you’re not allowed to be outside for more than 24 hours. You know, Eisen is really far from here.” [Paula]: The restriction applies to refugees who are seeking asylum in Germany but whose asylum application has not yet been processed, and to tolerated persons. The Interviewees also tell us how it feels for them, living in their heim. By Heim the refugee accomodation is meant. [Stephan]: “Donc je veux juste dire en conclusion, on peut dire que… il faut voir que la majorité des Camerounais qui sont là-bas ne vivent pas dans le Sozialheim, parce que le Heim c’est ta maison. C’est quand tu es en Allemagne, quand tu es dans le Heim, le Heim c’est ta maison. Ça veut dire que tu n’as pas une autre maison en dehors du Heim, le Heim c’est ta maison. Alors tu ne peux pas être chez toi, tu es mal à l’aise. Il faut que tu viennes à Berlin pour te défouler un peu, pour aller voir les amis, ou bien peut-être aller dormir chez un de tes amis, parce que tu n’es pas à l’aise chez toi. [ENG] So I’d just like to say, to conclude, one can say that … you have to see that most of the Cameroonians who are there don’t live in the heim, because – the heim is your home. It’s, when you’re in Germany, when you’re at the heim, the heim is your home. That means that you don’t have anywhere else to live apart from the heim, the heim is your home. So you can’t feel at home, you don’t feel comfortable. You have to come to Berlin to relax a bit, to visit friends, or perhaps to stay overnight with one of your friends, because you don’t feel comfortable when you’re at home. [Jakob]: However, camps can also be perceived as places of balance, if they are well run. This is the case with Ana. [Ana]: So, I mean, most of the time you feel really uncomfortable when you’re in public places, but maybe when you’re in the camps where you’re blacks or you have other, more black people, then it feels a little bit easier. When you get outside, it’s really, it feels really awkward. It’s easier because you have your other black people and I would say the socials of the camps are a little bit helpful. (..) Yeah. (..) So, it’s kind of easy at the camps, but when you get outside, really it’s difficult. Okay. [Jakob]: All of our interviewees reported feelings of isolation and exclusion as well. Stephane, among others, told us how this has affected him. [Stephan]: “Je suis obligé de venir à Berlin tous les jours pour me sentir un peu à l’aise. Parce que quand je rentre là-bas, il faut seulement dormir. Faire quelque chose à manger, dormir, c’est tout. C’est quand je suis à Berlin que je sens un peu (…) que peut-être tu vis. Sinon, là-bas, il n’y a pas une vie. [ENG] I have to come to Berlin every day to feel a little at ease. Because when I go back there all I have to do is sleep. Make something to eat, sleep, that’s all. It’s when I’m in Berlin that I feel a bit (…) that you can have a life, perhaps. Otherwise, there, there’s no life. [Paula]: Discrimination and not feeling welcome at the accommodation have been brought up in almost every interview we took. However, discrimination is not only linked to the heim. Ana and William shared two experiences of everyday racism with us that happened to them while using the public transport: [Ana]: Another thing I would say is, sometimes, maybe, when you’re in the trains or in the bus, and, for me, I would say, like, I have my monthly ticket in my phone. So, sometimes, maybe the phone is a little bit slow, or it’s not opening the ticket, and the control comes, and you’re trying to tell them it’s a little bit slow, and, like, they feel like you don’t have the ticket, and you’re just doing this to, to maybe make them go away,or just, like, they’ve already have, you feel like they’ve already have a perception about you as a black person. So, maybe they feel you don’t pay the tickets, you’re always, like, they always feel like you, you always do everything wrong. [William]: “Oui. Déjà, une fois je rentrais de l’école, j’ai emprunté un bus au niveau de Berlin pour me déposer à l’école. À un stop, il y a une dame qui est entrée dans le bus. Et elle ne savait pas que je comprenais ce qu’elle me disait. Elle a parlé de me faire… que je quitte la place pour qu’elle puisse s’asseoir. Mais je ne l’ai pas regardée, je ne lui ai pas non plus parlé, je n’ai rien dit. Pourtant il y avait plusieurs personnes auprès de moi, elle ne leur a rien demandé. Et j’ai ressenti ça un peu comme, euh… T : …un peu raciste. W: Oui. T : Parce que tu étais le seul Noir. W: Oui, comme si j’étais très supérieur [gemeint ist wohl „comme si j’étais le tout premier à entrer en ligne de compte“] pour que ELLE s’asseye, pour que je doive me lever, quoi. T : Elle était venue directement vers toi pour te dire… W : Oui, vers moi, oui. T : Et dans le bus tu étais le seul Noir W : Bon, j’étais pas le seul Noir, mais j’étais le seul Noir assis, quoi.” [ENG]: “Yes. Once I was coming home from school, I got a bus in Berlin to get me to school. At one stop there was a lady who got on the bus. And she didn’t know that I understood what she was saying to me. She said that I … that I should give up my seat so that she could sit down. But I didn’t look at her and I didn’t speak to her either, I didn’t say anything. And yet there were several people sitting near me, she didn’t demand anything of them. And I felt that was a bit like, uhh … T: …a bit racist? W : Yes. T : Because you were the only Black person. W : Yes, as if she had singled me out so that SHE could sit down, so that I would have to get up, know what I mean? T : She came straight up to you to tell you … W : Yes, up to me, yes. T : And you were the only Black person on the bus W : Well, I wasn’t the only Black person, but I was the only Black person who was sitting down.“ [Paula]: The discrimination experienced by refugees often has serious mental consequences. There is a direct connection between physical isolation and psychosocial isolation here. we will also talk a little more about the effects of everyday racism on the feelings of our interviewees in our next episode. [Jakob]: we will hear about the meaning of public transport for refugees that live in physically isolated Shelters In a moment. But before that, Fiona explains to us in detail how isolated the Shelters are and what effects this has. [Fiona]: “So with the physical isolation, it’s not only being removed from possibilities of integration with normal German societies so that they can go shopping, go to schools, go to German classes. (..) And that takes a little bit extra work for them to access from the physical isolation, which is stressful already because, I mean, if you go and stick people in the middle of nowhere and they are foreign to that country, first of all, then it takes them much more sort of mental energy and physical energy to reach just normal, everyday life things” Paula: Fiona also talks about the actual distance between the shelters and the rest of society, emphasising the consequences. [Fiona]: “I think the closest (..) house from my von Heim was probably I want to say maybe three kilometres and it’s somebody’s holiday home so they were never there (..) the neighbourhood and the towns where these von Heims are, (.) there’s a feeling that they’re over there, they’re hidden, that place far, because they’re dangerous. (..) or they’re not ready to integrate or you are not supposed to integrate with them or even socialize with them. so you have done nothing but that feeling comes from why did the government choose that place so already the German has been isolated by the government by making him think that hey this place is so far it’s removed from the rest of the German communities and societies it’s good for this kind of people let’s put them there but just by mistake you are a neighbour (..) so you see the sociological impact so German people then think it’s so far away here must be a reason for it probably because it isn’t safe. And you see it’s a recurring theme it happens over and over and over again it’s not special to certain cities every town you go to in Brandenburg the Wohnnheims are very isolated so it’s logic to just think oops these are not very safe areas it’s not (..) very safe so let’s put them far from societies yeah” [Jakob]: Fiona pointed out that the residences are kilometres away from the train station and other houses. Theodore told us about having problems with the connection to public transport. He told us that he went to visit a friend living somewhere else in brandenburg, which became a huge problem in the end. [Theo]: “we have problems with trains and buses. At 8, 9 or 10, if you don’t get the possibility to come back, it is not easy for you to come back Because the last train is at 8 or 10. After 10, you don’t get the train. The bus comes at 10, 11 and 12. But sometimes you can’t see any bus. Once I went to visit my friend in Rathenau, I finished with my friend because we had an exercise to do together. (.) I finished around 10. I must take the bus to come to Bahnhof. In Bahnhof, I will take the train. The last train left, so I must take the bus. (..) I came and stayed in a stop place. The driver saw me. I waited for the bus. Normally, he stops the bus, he saw me very well, and he continued. (..) I was obliged to leave and work to come to Bahnhof.” [Paula]: According to Fiona, the fear of missing the last bus can have a particularly isolating effect on women. [Fiona]: “I mean I came from a von heim where someone froze to death in the winter women (…..) will especially women you hear that somebody died frozen in winter there’s no way I’m leaving the von heim after four o’clock (.) it’s the chance that I might be left by the train is just too high so you’re limited movement wise because you only have daylight to move (..) and (..) even that you’re not sure because the trains move at very specific times every one hour every one half hour so (..) you (..) can’t (..) really go far” [Paula]: Fiona states that Refugee women are particularly affected by physical isolation as well as other forms of isolation. [Fiona]: “to be a woman or a child a refugee living in those isolatedjoint accommodations (..) is (….) it’s it’scapital offense if you ask me (.) they (.) have fallen way under the cracks they are completely forgotten they’re not (..) no one thinks about them (.) they’re (.) so much far off affected all these reason we’re talking about than a normal (..) male (..) younger who has no children no family he has no responsibilities but only to self his life goes very differently than for a woman with children and refugee” [Paula]: Fiona also talks about the fact that many of the refugee women have experienced trauma and have been socialised differently. Nevertheless, they are expected to function fully and, in addition to the tasks imposed on them by the asylum system, they also have to take on care work. [Jakob]: These statements are also reflected in scientific findings. You can find the studies on this in the podcast’s source notes. One of these studies, published in ocotber 2021, focuses on the Spatiality of Social Stress Experienced by Refugee Women in first Reception Centers. It finds that: „in terms of the intercultural needs and practices of these women, social stress is triggered by a lack of essential privacy within the spatiality of these structures“ (S.1685) The study concludes that: „women were engaged in a constant struggle to understand and adapt themselves to life in these accommodations or modify their living conditions“ – „Due to various imposed legal restrictions, the spatiality of these structures hindered the performance of these women’s social freedom and agency.“ (S.1705) [Paula]: Another study by the Federal Ministry for Migration and Refugees highlights female refugees, older refugees and refugees with a low level of formal education as particularly vulnerable groups. The survey of several thousand people found that refugees, and female refugees in particular, are more affected by isolation and social loneliness than other population groups. Social isolation in this case is understood as a combination of a lack of contact and a lack of relationships But the physical accommodation also poses problems for our interview partners: Both the type of accommodation and the limited opportunities for employment and daily routines contribute to isolation. [Ana]: “Because you’re just, you’re in your room, you’re sharing a room with maybe eight other people, five other people. You’re just in your room, from your room, you go and take, have breakfast, come back, go have dinner, come back. I mean, if, uh, you have, you think a lot when you’re there.” [Stephan]: “Donc moi, si ce n’est que moi, je reste à [place], parce que… C’est pour ça que la majorité des gens, là-bas, n’habite pas à [place]. Je connais… Il y a les chambres que tu as, il y a une personne, alors qu’il sont trois. Parce que personne n’est là. C’est pas vivable.” [ENG]: So if it’s just me, I stay in [place], because … That’s why most people, there, don’t live in [place]. I know … There are rooms where you have, there’s one person, although there are three. Because nobody’s there. You can’t live like that. [Jakob]: Let’s take a quick look at how the rooms inside of the shelter are allocated. We have already mentioned that refugees have no say in the decision about which shelter they will be accommodated in, but is there a difference when it comes to rooms and roommates? [Palua]: There are ceratin rules by which refugees are being given a room: Married couples or families have the right to live together in one room. Women may only be accommodated in rooms with other women. There is a right to a lockable room and a key. If you share a room with other people, you have the right to a lockable cupboard. In general, however, you have no say in which room you are accommodated in. People who have come to Germany alone cannot choose who they have to share their room with. There are also rules designed to protect the privacy of refugees. The home management is not allowed to enter their room without their permission. Room inspections in their absence or without prior notice are not permitted. They have the right to receive visitors during the day. If they are absent overnight, they must inform the home management. If they are absent for more than three days, the home management may assign their room or bed to another person. Their personal belongings must be stored. [Jakob]: As we mentioned: Refugees cannot always choose who they share their room with, which can lead to problems: [William]: “Oui, déjà avec mon collègue de chambre, lui il se permet de toucher à mes affaires sans mon accord et ça ne m’arrange pas, je le lui ai reproché plusieurs fois. Et je compte me plaindre au Sozialarbeiter, parce que même d’ailleurs ce matin je me suis rendu compte que je n’avais pas ma montre à l’endroit où je l’avais posée. Mais lui, il est déjà sorti pour le travail, j’attends qu’il rentre. Et je l’ai averti pour une prochaine fois, parce que ce n’est pas la première fois qu’il touche à mes affaires, et je lui avais déjà interdit d’y toucher sans mon accord. Lui, avec mon co-chambrier, j’ai un peu ce souci-là actuellement.” [ENG]: Yes, with my room-mate. He touches my things without my permission and I don’t like that. I’ve told him off for it several times. And I intend to complain to the social worker because this morning I also realised that my watch wasn’t where I had put it. But he had already gone out to work. I waited for him to come back. And I warned him for the next time, because it isn’t the first time that he has touched my things and I had already told him not to touch them without my consent. With him, my room-mate, I have that problem a bit at the moment. [Jakob]: Physical isolation serves as a link between other forms of isolation and exclusion. From our interviews, we conclude that spatial isolation has an impact on both mental health and access to information, and thus on the ability to live independently. Fiona expresses both of these points: [Fiona]: “already you can see the breakdown of their self-confidence starts from the heim. Yeah. So you can imagine with what is going on with the racism and the escalation of racism in Brandenburg. If things are like this right where you live, how much more worse does it get outside the heim? Yeah. It can only get worse. Yes. And then the other impression I had that made me a little bit worried is this access to German courses and to services like to find information where to get Ausbildungsplätze, Job opportunity, medical intervention. They have no access, they don’t know where to start. And you can see a lot of them sit and almost like they are left with no choice but to sit back So because you do not interact with the normal community, (..) information sort of like what you already know is what you stay with. (.) No new information comes in because you’re not going out really. And if you are, you’re going to the same exact places. It’s the Nettos, the ALDIs, the Lidls. There’s no information you can get there reallyHospitals are far. Schools are far. You know, just normal everyday things. Not to talk about job opportunities. (.) So you are really removed from information. And remember, these places are also far. So there’s no internet. There’s no connection. The connection to mobile telephone is also very weak. So you are very, very limited. You’re sort of cut off from reality.” [Paula]: And that brings us to the end of the second episode of our podcast isolated. From our interviews, we were able to identify the central role that physical isolation plays in the overall construct of isolation. Physical isolation occurs both through assigned, remote, living quarters and through the impossibility to decide independently how and where to move. We would particularly like to emphasise the increased impact on female refugees, who suffer even more from isolation. [Jakob]: The remoteness of the accommodation, but also the stigmatisation that comes with it, are not without mental consequences. More on this in the next episode! See you next time! Ending [Ana]: “at the end of the day, I am me. I can’t be you. I am black. I cannot turn into white to please you. At the end of the day, I have my own personality. I have my own person. I am my own person. So, really, for me, I don’t, I don’t, um, really think so much about it. But, of course, when it happens, yes, there’s a way you feel. You can’t deny that.” [William]: Je voudrais que les Allemands et les étrangers vivent comme des frères. (.) Et n’aient pas de haine. Peut-être pour quelque chose qui s’est passé il y a 100 siècles. (…..) [ENG]: I want Germans and foreigners to live as brothers. (.) And not to hate each other. Perhaps for something that happened 100 centuries ago. (…..) Acknowledgements [Paula]: We would like to thank: Refugees Emancipation for their tremendous support of the project, the connections, and their work. Special thanks go to: Fiona Kisoso, Immaculate Chienku, Louise Nzele, and Eben Chu We also thank our interview partners: Ana, Stephane, Theodore, and William for their trust and cooperation! Thanks to Tobi, Theo and Anna for the voice-over. A big thank you to Yohane Nkuibo, Max Guggenheim and Deirde Winter for translating the French interviews. For mixing and technical assistance, we thank Johannes Tuchelt [Jakob]: Isolated is a podcast produced by Paula Küntzel and Jakob Tuchelt in cooperation with Refugees Emancipation, for the Department of Social Structure Analysis at the University of Potsdam.

Dieses Bild hängt mit folgender Bildunterschrift im Refugees Emancipation Community Center:

As in Kunersdorf, people in Hohenleipisch live in old isolated buildings in the middle of nowhere. Can you imagine coming home to those conditions every day?

Wie in Kunersdorf leben die Menschen in Hohenleipisch in alten, abgeschiedenen Gebäuden mitten im Nirgendwo. Können Sie sich vorstellen, jeden Tag unter diesen. Bedingungen nach Hause zu kommen?

Folge 3: Pyschosocial Isolation

Transkript des Audios

Podcast-Script: Isolated– Isolationserfahrungen von Geflüchteten in Brandenburger Unterkünften Ein Podcast von und mit Paula Küntzel und Jakob Tuchelt

Folge 3

Teaser:

[Fiona]: “i’ve always said this and i will keep saying it until heims are abolished the heim is a trap and not just a physical trap it’s an emotional and psychological trap”

[Ana]: Yeah, and you don’t have a working permit, you don’t have anything, plus, you can’t work if you’re, another thing, you can’t, you’re not allowed to work if you’re in the first reception center.

[Theo]: “Many nightclubs, when you come, you are a black man, it is not easy for you. Once I tried to go to see the atmosphere, but I didn’t receive a good appreciation. (..) So I don’t go anywhere now.”

[Ana]: “So, what makes us, makes us different? So, you’re just like, ah, maybe it’s because we are blacks and they are white. […] So, I mean, that, you just feel, maybe, racism or, or, uh, she’s just, uh, I don’t know how to put it, but, if, for lack of a better word, racism at its peak.”

[Fiona]: “so there’s that dependency which is actually very unhealthy because you stop you stop having dreams and self determination […] you become dependent so exactly what a lot of refugees are running away from their homes that dependency of aid and just you know that saviorism you come and replicate it her”

Introduction

[Jakob] Welcome back to episode 3 of our Podcast Isolated- a Podcast about isolation experiences of refugees in Brandenburg. I’m Jakob.

[Paula:] And I am Paula, and we study sociology at the university of Potsdam.. Looking Back into the last Episode:

[Jakob] In our last episode we talked about our trip to a refugee shelter and about physical isolation.

Today, in the third episode, we will deal with the topic of psychosocial isolation.

[Paula]: All people we interviewed for this podcast on their personal experiences were anonimized by us and are being reffered to under a fake name.

[Jakob]: We have to adress that both Paula and me are white and, like our parents, were born and raised in Germany. Accordingly, we have never had to experience racism restricting our lives or our everyday routines in any way.

Topic of this Episode

[Paula]: As already said, In this episode we will talk about psychosocial isolation. But what do we mean by psychosocial isolation? [Fiona] explains this from her professional point of view.

[Fiona]: And then there’s a psychosocial aspect of it that, first of all, the neighbourhood and the towns where these Wohnheims are, (.) there’s a feeling that they’re over there, they’re hidden, that place far, because they’re dangerous. (..) or they’re not ready to integrate or you are not supposed to integrate with them or even socialize with them. So there’s that mental block. Then there’s also the feeling that normal things, determinations and dreams and hopes for human life, you know, that you want your children to go to good schools or to be in good neighbourhoods, safe neighbourhoods, that you determine what kind of life you want to live. But all this has been taken away. You sort of like just have to take it without questioning. (.) So why I call it psychosocial is because it’s already been put in your mind that you have no choice. (..) You just take what we give you and be quiet and just do not complain. So you will see a lot of people who live in these kinds of accommodations sort of just go unnoticed. They don’t want to participate in community building, in political work. They’re basically non-existent. They’re faceless. They’re voiceless because of the isolation [Jakob]: As you can hear, there is a mental effect from the physical isolation, which we already adressed in our last episode. In this episode we will talk about the instance that psychosocial isolation works in two directions: On one hand, the german civil society is mentally isolated from the refugees, because of spatial isolation of refugee shelters, amongst other types of isolation. On the other hand, refugees are mentally and socially isolated from participating in society and prevented from building and keeping strong connections to each other.

[Paula]: In this episode our interviewees will tell us closer how they feel living in germany and in the refugee accomodation. They´ll talk about their everyday structure and experiences of racism, about their oppinion on working permits for refugees, live chances, health and mental health, lonelyness and relationships, their impressions of germany and german people, and about belonging. We have asked all interviewees what it generally fells like living in germany to them.

[Stephan]: “Bon, je veux d’abord dire une chose, c’est que je peux pas dire que je me sens mal, parce que quelque part l’Allemagne m’a accueilli et elle m’aide avec le social mais… bien vrai, moi je suis beaucoup triste en Allemagne parce que, je sais pas, euh…, la solitude c’est quoi, c’est que là où je vis dans mon Heim, là où je vis…”

[ENG]: Well, first I’d like to say one thing, and that’s that I can’t say I feel bad, because in a way Germany has taken me in and it is helping me with the social benefits but … it’s true, I am sad a lot in Germany because, I don’t know, uhh …, being alone, it’s, you know, it’s that where I am living, in my hostel, where I live …

[Ana]: “Well, living in Germany and Brandenburg as a refugee is not something very easy.It has a lot of challenges, especially being that you don’t understand the German language and maybe the culture. (.) It’s a little bit of a challenge there because most of the time, even when you want to just buy maybe something to eat, it’s a problem having to express yourself and all that. Plus, you always just feel like people look at you weirdly. So, like, someone, no one is really, really willing to listen to you, you know, and, plus, you can’t really express yourself well in the German language, so, you know, you don’t really have much of a bargaining chip.(…) So, yeah, everyday life in Germany? (..) No. (….) It has quite a bit of challenges, yeah.” [Paula]: The interviewees also tell us how they feel about living in the Heim. By Heim the refugee accommodation is meant.

[Stephan]: “Donc je veux juste dire en conclusion, on peut dire que… il faut voir que la majorité des Camerounais qui sont là-bas ne vivent pas dans le Sozialheim, parce que le Heim c’est ta maison. C’est quand tu es en Allemagne, quand tu es dans le Heim, le Heim c’est ta maison. Ça veut dire que tu n’as pas une autre maison en dehors du Heim, le Heim c’est ta maison. Alors tu ne peux pas être chez toi, tu es mal à l’aise. Il faut que tu viennes à Berlin pour te défouler un peu, pour aller voir les amis, ou bien peut-être aller dormir chez un de tes amis, parce que tu n’es pas à l’aise chez toi.“

[ENG]: So I’d just like to say, to conclude, one can say that … you have to see that most of the Cameroonians who are there don’t live in the heim, because – the heim is your home. It’s, when you’re in Germany, when you’re at the heim, the heim is your home. That means that you don’t have anywhere else to live apart from the heim, the heim is your home. So you can’t feel at home, you don’t feel comfortable. You have to come to Berlin to relax a bit, to visit friends, or perhaps to stay overnight with one of your friends, because you don’t feel comfortable when you’re at home.

[Jakob]: In housing studies, the question of what exactly constitutes a home is a much-discussed topic. A distinction is often made between concepts relating to space and those relating to place. Professor Hazel Easthope, University Sydney writes the following in a review article on different Theories about the topic : The Title of the article is ‘A Place called Home’:

„While homes may be located, it is not the location that is ‘home’. Instead, homes can be understood as ‘places’ that hold considerable social, psychological and emotive meaning for individuals and for groups […] home is “a key element in the development of people’s sense of themselves as belonging to a place A home therefore is much more than just a place. Based on this definition, it quickly becomes clear that refugee shelters are often not places that offer the opportunity to develop a sense of home. Fiona puts this in a bigger context and adds what in her view would be necessary to change that bearing down situation.

[Fiona]: “I’ve always said this and i will keep saying it until heims are abolished the heim is a trap and not just a physical trap it’s an emotional and psychological trap yeah because to it’s putting humans in uh confinement and and putting them in situations where so much is isolated or removed or they’re they’re there’s so much distance between them and making their lives better or uh determining for self what where which direction their lives will take so it’s almost like when you come to a heim they take away the hope they take away faith they take away beliefs they take away you know possibilities to just determine for yourself as a as a human being”

[Paula]: These issues, adressed by Fiona, we will explore further in this episode. Living in shared accommodation has a direct impact on how everyday life is structured. We remember, for example, curfews and other restrictions.

However, the feelings that arise are not only linked to the heim, but also affect the everyday life of refugees. Stephane shared his daily routine with us:

[Stephane]: “Et moi je vis vraiment du jour au jour là-bas parce que je ne me sens plus en sécurité tandis que je pars à l’école à 17h15, finis à 20h. Et quand je rentre, je dors. Or, ce qui n’est pas normal.”

[ENG]: And there I really live from one day to the next because I don’t feel safe anymore, whereas I leave for school at 5.15 p.m. and finish at 8 p.m. And when I get back, I sleep. The social worker doesn’t say hello. That’s not how it should be.

[Jakob]: As important caregivers, social workers play a central role in the accommodation centers! In our next Episode „Isolation of Information“ we´ll take a closer look on the key role of social workers.

[Paula]: Theodore also tells us about his living experience in Germany. For context, we have to add, that he wanted to start a german course but didnt get an answer on his application for one year. He will speak about „social“ and „ausländer“. By „social“ the social sevices are meant and by áusländer´ the immigration office, (which is „Ausländer-Behörde“ in german)

[Theo]: “In Germany, it’s busy. Before, when I explained to you, I was alone in my room because I didn’t start the course. Sometimes I felt stress. Sometimes I take a bus or train. I go to Berlin, I visit the city and I come back. Every time I have my phone, I call my family in my country, talk with them.

I have also one niece in Berlin, sometimes two or three months. I go to meet her. I spend one or two days with her and I come back.(..) Sometimes I receive a letter from a social or from an outlander. I go and I talk with them. I come back after I start the course. I have a course every day. My course starts Monday and finishes on Thursday. From 8 o’clock to 11 o’clock. I go from Monday to Thursday, I go to school. (..) When I come back, I start my course. Sometimes, if I feel I was tired, I see the film on my computer. I sleep. (…) This is the same thing every day41-. | After I meet Mr. Cho, because in my country, I lead an organization. I’m the president of my organization.”

[Paula]: Except for that, Theodore does voluntary work, once a week.

Stephan continues to tell us about his everyday live.

[Stephan]:Je suis obligé toujours de venir à Berlin, parce qu’on se sent frustré, et c’est un peu ça que moi je vis, mais sinon à ce niveau, moi je ne me plains pas, parce qu’en Europe chacun fait sa vie, chacun fait ce qu’il veut, donc tu n’as pas le droit de regarder ce que l’autre fait, ou bien ce que tel fait, donc, à ce niveau, moi je n’ai pas de problème, parce que moi je sors, je suis d’abord chez moi, je sors, je vais à l’école, quand j’ai fini l’école, comme j’ai dit c’est vendredi, j’ai fini l’école, j’ai fini l’école, je vais aller à la vie, bon, après ça je rentre chez moi et je pars dormir, donc en un seul mot pour dire c’est que quand je suis chez moi, je suis chez moi, quand je sors, je ne veux pas les contacts avec les gens, et puis en dehors du petit avec qui je cause bien mes anciennes relations, (unverständlich, vielleicht „comme tel était“) Eisen[hüttenstadt] ou bin (unverständlich), je vais chez la Camerounaise(das ist wohl eine von einer Kamerunerin betriebene Kneipe), boire souvent, je bois ma bière, je rentre chez moi. [ENG]: I always have to come to Berlin because you feel frustrated and that’s a bit what I’m going through, but otherwise on that level, I’m not complaining because in Europe everybody makes their own life, everybody does what they want, so you don’t have the right to look at what other people are doing, or what a particular person is doing, on that level I don’t have a problem because I go out. First I’m at my place, I go out, I go to school, when I’ve finished school, like I said, it’s Friday, I’ve finished school, I’ve finished school, I’m going to start living, okay. After that I go home and I go to bed. But in a nutshell it’s: when I’m at home, I’m at home, and when I go out I don’t want to meet with people, and then, apart from the boy I talk to, okay, the people I used to hang out with, like in Eisen[hüttenstadt], I go to the Cameroonian bar for a drink, often, I drink my beer, I go home again.

[Jakob]: According to figures from the Research Report 50 of the SOEP refugee Survey which [Ana]lyses data from 2017 to 2021, 20% of refugees often or very often felt socially isolated, compared to only around 6% of people without a migration background.

Social isolation in this case is understood as a combination of a lack of contact and a lack of relationships: refugees are more affected by a lack of relationships than other population groups. 14.2% of refugees have no close contact person.

Contact with Germans is particularly lacking among refugees living in shared accommodation. A fact that underscores [Fiona]s statement of double isolation, i.e. the isolation of refugees from Germans and vice versa.

All interviewees also tell us of experiences of racism that they have made in different areas of their everyday live. Some of them on a regular basis.

[Ana]: “another thing in school, because now that, that is where I’m, I interact with, maybe most, mostly other people from other countries, and, uh, for example, in my school, my teacher is Ukrainian, and, uh, in my class we, uh, three blacks. (.) I’m the only black lady and, uh, two other boys. (..) The way, and then most of my classmates are Ukrainians. Yeah. So most of the time they talk in Ukraine with the teacher. Mm-hmm. Uh, uh, sometimes when, uh, I feel like this is not something I’m making up, it’s something that has happened. The, the, one boy, one black boy was sick one day. He wasn’t really feeling so well in class and he wanted to go home. And he asked the teacher if he can go. And the teacher was like, no, no, you know, you have to, if you have, if you must go then you have to go and report to the office and all that. And this boy was really feeling bad. Mm-hmm. So, then the boy left him to go and talk to the people at the office and I think he didn’t find anyone. So he came back and he was like, just let me go. No, I can’t, you know, you have to inform the, the office that you’re.(.) Then, this happened also with one Ukrainian boy. Um, she left the class and went with the boy to the office to try and tell, because this, this Ukrainian boy also doesn’t speak good German. (.)Mm-hmm. Um, two, just to explain what’s up with the boy. (.) Mm-hmm. (.) To the, to the office guys. And then he came back. He even helped him to put his things in the bag and left the class. So, you know.”

[Jakob]: We were also told about experiences of racism during freetime activities. Theodore tells us that black people are usually not allowed into nightclubs.

[Theo]: “So when we come to the weekend, they accepted many people, but when we come, they told us that it is a private reception or something. (.) I asked my friend, I have one friend from Chad, I asked him, he told me here there are one or two, only one or two nightclubs who accepted black men. (.)

[00:15:55] Many nightclubs, when you come, you are a black man, it is not easy for you. Once I tried to go to see the atmosphere, but I didn’t receive a good appreciation. (..) So I don’t go anywhere now. When I go to school, I come back. Sometimes if I want, I go just to visit the city, I walk, I see the buildings, I see the place, the park, and I come back.” [Paula]: Lets bring in a little Data, to back things up:

Every two years, the German Center for Integration and Migration Research (DeZim) publishes the National Discrimination and Racism Monitoring Report.

This is a survey of over 9,500 people who, among other things, provide information about their personal experiences of discrimination. However, we must emphasise that this data does not explicitly refer to refugees!

Nevertheless, the majority of the characteristics relevant to the report also apply to refugees! A distinction is made between subtle discrimination (e.g. unfriendly behavior, being stared at, or not being taken seriously) and openly offensive discrimination (e.g. insults, harassment, threats, or physical attacks).

54%, or one in two, of the respondents who identified themselves as racially marked stated that they experienced discrimination at least once a month. In particular, Muslim (61%) and Black women (63%) as well as Black men (62%) experience increased subtle forms of discrimination.

These experiences are very real personal experiences that determine the everyday life and future of those affected! Ana shares with us a very specific situation and an attempt to find a way to deal with it. At the beginning, she refers to how the teacher in her language course treats students differently.

[Ana]: “So, what makes us, makes us different? So, you’re just like, ah, maybe it’s because we are blacks and they are white. Mm-hmm. (..) So, and it doesn’t, she doesn’t just do that to the Ukrainians because she’s Ukrainian, even the other white people, the Arabs and all that. She treats them, she treats them differently from the way she treats us. (.) So, I mean, that, you just feel, maybe, racism or, or, uh, she’s just, uh, I don’t know how to put it, but, if, for lack of a better word, racism at its peak. (…) Yeah. (…) So, that is how isolated we feel. (.) Or, sometimes when you go even to the supermarket, you, you want to ask for help on, like, one time I’m, I didn’t know how to use the bread cutter at the supermarket. Mm-hmm. And I wanted to buy bread, then I called the attendant. One attendant actually ignored me, like, literally just ignored me. Mm-hmm. (…) So, then, uh, so, I just stood there and I’m like, okay, I really need this bread. Well, I can’t carry it like that without, because it’s, I just didn’t know how to use the machine. Which is not a crime. No. No. (..) So, the attendant ignored me then, one, one attendant then came across and, you see, you see, the way you’d approach someone and say hi, you say hi to someone and they don’t respond to you. Mm-hmm. Wow. (…) And, she just told me, what do you want? Mm-hmm. And I told her, I, I need your help with, I want to buy bread and I need your help with the slicer, can you help me? And she didn’t talk, she just came and pressed those things and, she asked me, which bread doyou want? Then I gave her the bread. And she just put it there and she told me, if it’s done, this is what you do and get it off, okay. (…) Mm-hmm.(…) So, you see, the, like, those are, uh, just a little, some of the challenges we go through. And, I mean, as a person you really feel, I mean, there’s a, there’s just a certain way you feel about it.Mm-hmm. And, really, it makes you feel so, so bad about yourself. Because, what do you mean, you’re, I’m, I’m saying hi to you, it’s, it’s, it’s, it’s, a harmless hi. I mean, you just find a way to live with it now that you’re in the white man’s land, you just find a way to live with it. Most of the time, like, me personally, I would say, I really don’t let these things really get into me that much, but, you see, when it happens, when it happens firsthand, there’s a way, definitely, you’ll feel about it. But, for you to have a peaceful life here, you really have to just find a way to cope.”

[Jakob]: The experiences continue, Theodore tells us of his search for a flat.

[Theo]: “I don’t like my situation. (..)For this reason, I prefer to get an apartment. (.) Now I get money from here, for my social benefits. I can pay for the apartment if it’s not expensive. (.) I asked my niece if she could take the apartment with her name, and I would pay her. (..) She agreed. When she started the process, she spoke Deutsch normally, very well. (.) She started to call the woman, she talked with her. At the beginning, she thought that my niece was a Deutsch. She was friendly with her. But after she asked her what her country was, my niece told her that she was from Chad. (..) She changed her mind. She said that the apartment was not free for her only. There were many other people who applied for that. (…) She wanted to meet her and talk with her during her interview. (.) It was a long process, after she refused to give us the apartment. (..) I explained her situation to one guy from my IM. (..) He told me that this situation was not the first. (…) He had applied for an apartment before. But when a black guy applies for an apartment, he comes with his documents. He will call you if he gets the new apartment. There were no free apartments. But if he gets the new apartment, or if someone leaves his apartment, he will call you. You don’t receive a call from them. (.) But if it is a Ukrainian or Arab guy, you can get an apartment easily. (..) He gives them the documents before. After him, many people from Syria and Ukraine come and get apartments. When he comes back to ask them what the problem is, he says that he has applied here for a long time. But many people after me get apartments and don’t call me. They say that it is not a problem, they don’t get free apartments, you can wait. (…..) This is another reality for us. To get an apartment here is not easy. (…..)”

[Jakob]: Stephan tells us about a young man and how he was denied an important document

[Stephan]: „J’ai même une petite anecdote, pour dire vrai. Il y a un petit là-bas qu’on appelle Grisse, un jour il est venu pour demander son papier du social. La maman lui a dit que non, elle ne lui donne pas le papier du social. Il a dit qu’il partait à la police. C’est quand il est sorti pour aller à la police que la maman a senti que la police pouvait venir demander, l’interpeller, „pourquoi tu n’as pas voulu?“. Parce que c’est notre droit. On n’est pas arrivé là par hasard. Ça veut dire que si on est arrivé là, il y a un budget pour ça, pour nous gérer. Et maintenant quand tu sens que ton droit, tu ne peux pas avoir ton droit. Moi j’estime qu’elle était obligée de rappeler le gars. Le gars est revenu, elle a dit que non, attends, je vais te donner le Termin. Donc, je ne sais pas…”

[ENG]: I even have a little anecdote, to be honest. There is a boy there that people call Grisse. One day he came to get his paper from the social welfare office. The woman told him no, she wouldn’t give him the social welfare paper. He said he would go to the police. It was when he went out to go to the police that the woman realised that the police could come and ask, question her, «Why did you refuse?». Because it’s our right. It’s not by chance that we are here. That means that if you have arrived here, there’s a budget for that, to m[Ana]ge us. And now when you feel that your right, that you can’t get your right. In my view she was obliged to ask the guy to come back. The guy came back, she said no, wait, I’ll give you an appointment. So, I don’t know …

[Jakob]: All these experiences of everyday racism shape the reality of life for refugees. Later on, we will talk about the impact this can have on mental health. But first, let’s look at a specific issue that is often raised as an accusation:

Refugees are often accused of not working. Fiona links the feeling of living in a heim, the impact of racism and the connection to jobs and training places.

[Fiona]: “already you can see the breakdown of their self-confidence starts from the heim. Yeah. So you can imagine with what is going on with the racism and the escalation of racism in Brandenburg. If things are like this right where you live, how much more worse does it get outside the heim? Yeah. It can only get worse. Yes. And then the other impression I had that made me a little bit worried is this access to German courses and to services like to find information where to get Ausbildungsplätze, Job opportunity, medical intervention. They have no access, they don’t know where to start. And you can see a lot of them sit and almost like they are left with no choice but to sit back.”

[Paula]: We will speak about the access to information in more depth in the next episode. Where does this accusation that refugees don´t want to work come from? To understand this, let us take a look at the legal situation.

Working conditions inside the camps are ruled by the „Asylumseekers benefits act“, a law which by the way is only accessible in german language, which is why we had to translate it by ourselves. On a Sidenote: The Case that important documents such as ruling law etc. are not accessible in langauages spoken by refugees is something that occured plenty of times during our research.

Paragraph 5 of said act deals with working opportunities. Refugees who are able to work, are not employed, receive social funding and are no longer of school age may be required under this paragraph to perform minor tasks in their accommodation shelters or in the commune. [Jakob]: For these activities, they receive a statutory expense allowance of 80 cents per hour. The number of workinghours is 4 hours per day. If they refuse to perform a assigned activity, this is punishable with cuts in social funding. This paragraph, and especially the latest change in february of 2024, requiring refugees to perform community service such as raking leaves, is the subject of debate. Refugee councils and social workers are particularly critical of the fact that this law pretty much forces refugees to carry out work assigned to them. Since they are being left with no choice but to perform the tasks, in order to avoid punishment.

[Paula]: A very recently published study at the IAB, which is the Research Institute of the Federal Employement Agency, finds, that in fact the majority of refugees who came to Germany in 2015 are by now under employement. In Brandenburg 49% of the refugees who arrived in 2015 work currently.

At the same time it is important to understand that most refugees are subject to a general ban on regular employment, a topic which we will come back to in a moment! Many refugees who want to do regular work, very often fail to do so due to legal barriers.

[Ana]: “Yeah, and you don’t have a working permit, you don’t have anything, plus, you can’t work if you’re, another thing, you can’t, you’re not allowed to work if you’re in the first reception center.Mm-hmm. I think, maybe, they can just give work permits for people who would like to work. People who would, uh, like to go outside and work.Mm-hmm. They should just allow, give work permits.

Yeah, sometime, maybe they can just allow people to do these small jobs also at the camps. Yes, that is there, but, um, I understand some people don’t want to work and all that,but, yeah, they should give more of those, uh, small jobs. The cleaning jobs. The, yeah, most of the times it’s the cleaning jobs. Yeah. That’s what they are doing, but, I don’t know, maybe they could do it in, um, I don’t know(…) how to put it. (…….) Maybe pay a little bit more.“

[Jakob]: Now it gets a little more complicated, because we are dealing with the legal framework for work permits in general:

[Paula]: Asylum seekers who have received a positive decision on their asylum application from the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees are allowed to work in Germany without restriction. The same conditions apply to them as to Germans. Companies do not have to observe any special requirements when hiring asylum seekers.

In 2024 13.2% of the made Decisions on applications for asylum permitted a right to asylum. In February 2025 a decision on asylum took 12.3 months on average.

[Jakob]: Asylum seekers whose asylum proceedings have not yet been completed and those who have been granted temporary residence permit, are not allowed to work at all during the first three months of their stay in Germany. During this period, they are subject to an employment ban. After that, asylum seekers and tolerated persons generally have subordinate access to the labour market. To obtain specific employment, they must apply for a permit from the local immigration authority, which in turn must request approval from the Federal Employment Agency.

[Paula]: There are two criteria for approval by the Federal Employment Agency: the labour market test and the priority test.

The priority test clarifies whether the specific position can also be filled by Germans or foreigners who are registered as looking for a job, and have an unlimited working permit. The priority test is no longer required after 15 months of residence in Germany, afterwards tolerated persons generally have the same access to the labour market as asylum seekers.

[Jakob]: However, tolerated persons may be subject to an employment ban. During apprenticeship, tolerated persons have a guaranteed right of residence.

[Paula]: The minimum wage applies to refugees with unrestricted working permits, we remember: this means that their appliation on asylum has been accepted. Refugees without a working permit, meaning their application is still being processed or they have a temporary residence permit, can be employed under the circumstances we discussed earlier: Meaning 80 cents per hour and a punishment if they refuse the task!

[Jakob]: Since asylum applications often take much longer than a year to process, and only a fraction of applications are actually approved (in 2024, the figure was 13%), for the vast majority of refugees there are way more obstacles to get a job than for germans.

But it is not only legal hurdles that stand between refugees and employment: Fiona explains to us what aspects of mental blockage there are that make it so difficult to get a job.

[Fiona]: “Oh, if you’re that isolated from basic necessities and of course the physical block from not just yourself to Germans, but Germans to you, who’s going to give you a job? (.) Even the confidence to say, hey, I may look different, I sound different, I don’t speak the language, I’m new in this country. Okay, I’m going to go and search for a job and do an interview. You need to be a very crazy person to overcome all those blocks.”

[Paula]: The risk of social isolation decreases significantly as a result of starting employment or education. Figures from the Research Report 50, show a corresponding reduction of about 4 percentage points in the risk of lack of contact in general, and about 17 percentage points in the risk of lack of contact with Germans. In addition, data shows a direct correlation between the improvement of German language skills and participation in the labor market. Participation in employment and education is therefore one of the most important factors that can counteract social isolation and loneliness among refugees. Unfortunately, the widespread opposite leads to a long period of stagnation.